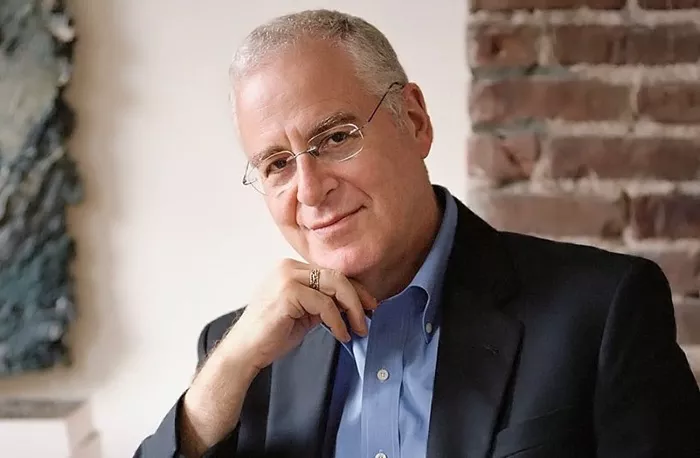

Renowned historian Ron Chernow, widely celebrated for his biographies of American icons such as Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, and Ulysses S. Grant, has turned his attention to one of America’s most beloved literary figures: Mark Twain.

Chernow’s latest book, Mark Twain, a comprehensive 1,200-page biography, was published this week. This marks Chernow’s first major release since his 2017 biography of Ulysses S. Grant and represents a significant departure from his previous focus on business magnates and political leaders to a literary giant.

Throughout his career, Chernow has earned numerous accolades, including the Pulitzer Prize for Washington: A Life, the National Book Award for The House of Morgan, and the National Book Critics Circle Award for Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr.

The idea to write about Twain has long fascinated Chernow, dating back to the mid-1970s when he saw Hal Holbrook’s portrayal of Twain on stage in Philadelphia. “There he was, with the white suit and cigar and mustache, tossing out one hilarious line after another,” Chernow recalls. Among Twain’s memorable quips, Chernow highlights the satirical jab: “There’s no distinctly Native American criminal class, except Congress.”

Chernow’s biography delves deeply into Twain not just as a novelist but as a public personality and cultural commentator—“the pundit, the platform artist,” as Chernow describes him. Though more accustomed to writing about verifiable facts than literary imagination, Chernow found personal connections with Twain, particularly as both experienced the loss of their wives and maintained careers as public speakers and professional writers.

The biography examines Twain’s frequent financial struggles despite his literary success and his wife’s inherited wealth, as well as the author’s involvement in various failed business ventures. Chernow also addresses a more controversial topic—the elderly Twain’s close friendships with adolescent girls, whom he affectionately called his “angelfish.” Chernow contextualizes these relationships, noting that while considered eccentric at the time, such behavior is viewed with discomfort today.

“Twain’s behavior was chaste and none of the angelfish or their parents ever accused him of improper or predatory behavior,” Chernow said. “At the same time, there was such an obsessive quality about Twain’s attention to these teenage girls—he devoted more time to them than to his own daughters.”

In an interview at his Upper West Side apartment, Chernow discussed Twain’s family dynamics, politics, and inner turmoil. He reflected on Twain’s criticism of political figures like Theodore Roosevelt, whom Twain derided as egotistical and attention-seeking. Twain famously described Roosevelt as the “Tom Sawyer of the political world,” likening him to a circus clown performing for an audience.

Chernow also explored Twain’s complicated relationship with his children, especially his middle daughter Clara, who struggled with living in her father’s shadow. Clara reportedly felt diminished in his presence, describing moments when she felt “reduced to the level of a footstool,” overshadowed by Twain’s dominating personality.

Regarding Twain’s marriage to Olivia Langdon, Chernow emphasized it was a genuine love match. “There was not a single day of his marriage that she didn’t say, ‘I worship you,’ ‘I idolize you,’” Chernow said, citing Olivia’s letters. However, he noted the irony that while Twain fiercely criticized the wealthy elite, he simultaneously aspired to join their ranks.

Chernow also touched on Twain’s personal struggles, describing a man who masked deep sadness with humor. “There’s a tremendous amount of self-loathing in him,” Chernow said, quoting Twain’s admission that, like poet Lord Byron, he detested life because he detested himself. “Mark Twain fit the stereotype of the funny man who’s sad and depressed under the surface, releasing that through humor.”